Bal Bullier | Sonia Delaunay | 1913

With a recent retrospective of her work at the Tate Modern in London, the work of Sonia Delaunay is revalued again after decades of ostracism.

The life of the artist seems to have been marked by a natural spontaneity to adapt to her environment. Born into a wealthy family in Ukraine, Delaunay spoke different languages, moved frequently and did not hesitate to marry a secretly gay gallery owner, who she divorced on good terms, to avoid the pressures of her family. But it is true that, as she could naturally adapt to the environment, she also possessed a gift to challenge conventions to provoke others.

In the early twentieth century, there is no doubt that Delaunay represented, herself, the modern times. In this sense, for instance, she believed that art should not be irrevocably subscribed to the formal categories, such as sculpture, painting, writing, etc. Her first abstract work is, in fact, a cover blanket for her baby’s cradle. This blanket, present in the Tate’s exhibition, consisted of geometric patchwork of different colors with a cubist feel. Delaunay did not distinguish between “high” or “refined” art from other that was not. So she developed his work regardless of the medium, and she painted from dresses to cars.

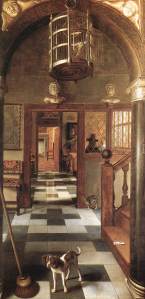

Art, for her and her second husband Robert Delaunay, was praxis. An adventure, a movement, an aesthetic. Various biographical sources mention that the Delaunays attended the parties in the Bal Bullier, one of the few Parisian dance halls that had electricity at that time, dressed in colorful, vibrant clothes, made by themselves. In this bohemian atmosphere in Montmartre, Sonia Delaunay met Picasso, the poet Apollinaire, and several of the Fauves, the “savages” of painting, from who takes the colorful fields of color that distinguished her work.

Art, for her and her second husband Robert Delaunay, was praxis. An adventure, a movement, an aesthetic. Various biographical sources mention that the Delaunays attended the parties in the Bal Bullier, one of the few Parisian dance halls that had electricity at that time, dressed in colorful, vibrant clothes, made by themselves. In this bohemian atmosphere in Montmartre, Sonia Delaunay met Picasso, the poet Apollinaire, and several of the Fauves, the “savages” of painting, from who takes the colorful fields of color that distinguished her work.

Her art, based on compositions of figures with intense color shows movement, rhythm, plasticity; and although her paintings had distinguishable shapes, like the one of the Bal Bullier Ballroom mentioned above; others were completely abstract, such as Electric Prisms No 14. That is why now Delaunay’s work is considered one of the few precedents of the abstract movement of later decades, which laid the ground rules of modern art.